Independent Review of the M/V Marathassa Fuel Oil Spill Environmental Response Operation

Chapter 1 - Introduction and context of the incident

Table of Content

1.1 Brief Summary of the operational response

According to the information available to the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG), the M/V Marathassa left the shipyard in Maizuru, Japan on March 16, 2015 to embark on its maiden voyage. The vessel then left Busan, South Korea on March 20, 2015 bound for Vancouver, with an expected date of entry of April 6, 2015.

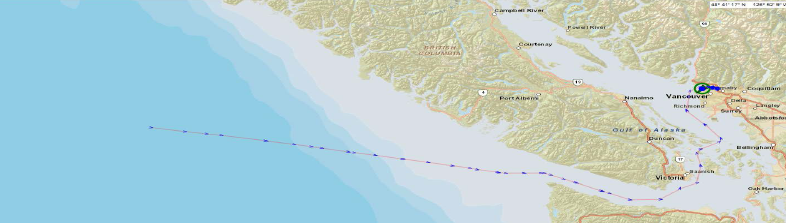

The M/V Marathassa entered the Vessel Traffic Zone, a regulatory zone extending to a limit of 12 miles off the coast of Canada, on the afternoon of April 5, 2015 and projected arriving in Vancouver on the morning of April 6, 2015. The vessel was making the transit in ballast, meaning without cargo. Upon seeking authorization to enter Canadian waters, the vessel had reported no defects or deficiencies in the hull, propulsion system, steering system, radars, compasses, anchors or cables. The vessel entered Canadian waters and followed the Traffic Separation scheme through the Strait of Juan de Fuca to Port Metro Vancouver (PMV). The M/V Marathassa arrived in English Bay, early on the morning of April 6 and proceeded to anchorage 12.

Automatic Identification System data tracking a portion of the M/V Marathassa's journey into English Bay

Late in the afternoon on April 8, at 16:48h, the CCG’s Marine Communications Traffic Services (MCTS) Centre received the first report of a mystery fuel oil spill sheen in the water, in English Bay close to an anchored deep-sea vessel, the M/V Marathassa. Several citizens from the Greater Vancouver Area reported similar observations in the minutes that followed, including one report indicating there were tar balls or fuel oil in the water. These reports initiated the assessment of the mystery fuel oil spill by PMV, and the subsequent regional and national response to the fuel oil spill by CCG, the Western Canada Marine Response Corporation (WCMRC) and its partners in Unified Command.

Marine oil spill response in English Bay, Vancouver involves many partners: the polluter or Responsible Party, CCG, Transport Canada (TC), Environment Canada (EC), WCMRC as the certified Response Organization, and PMV as per the Canada Marine Act and the associated Port Authorities Operations Regulations Footnote 9. These roles and responsibilities regarding oil spill response are further clarified in the Canada Shipping Act, 2001. While CCG has ultimate responsibility for ship-source and mystery-source spills in Canadian waters, a Letter of Understanding (LOU) between PMV and CCG provides further clarification on responsibilities in the port (referenced in Annex F). It indicates that the port will collect information in order to conduct an initial assessment. If a spill is determined to be recoverable, the CCG will assume command and control. Both parties have agreed to work closely through this arrangement and the model has been working successfully for numerous years.

Once the CCG received the initial pollution report, they contacted PMV at 17:04h to begin collecting information to inform the assessment. As a result of the large surface area the fuel oil spill covered, PMV: transited through the anchorages; collected information about the spill; deployed sorbent pads into the water to determine whether it was recoverable; viewed patches of dispersed sheens and recoverable fuel oil; and tried to identify the source. Assessments of the quantity of oil on the surface of the water can be challenging due to a person’s limited range of view. During this period the extent of the fuel oil spill was discussed amongst the port and CCG.

Notification of several key partners such as TC, EC and the Province of British Columbia (BC) occurred at 17:10h, although the provincial alerting criteria did not initially trigger cascading communications to First Nations, affected municipalities and other partners.

Based on aerial photos received by PMV from aircraft transiting the area at 19:27h, and subsequent discussions amongst partners that the fuel oil dispersion was extensive and recoverable in some areas, the CCG activated WCMRC at 19:57h to initiate an on-water response. WCMRC responded and had crew on scene one hour 28 minutes later and immediately began skimming the fuel oil off the water. As per TC’s Response Organization Standards Footnote 10, Response Organizations must mobilize resources within 6 hours after notification of the spill in a designated port. Additionally, the CCG has Environmental Response Levels of Service Footnote 11, requiring resources to be mobilized within 6 hours of the assessment. Due to the WCMRC’s strategically located assets in the port area, their response was well within the established standards.

The CCG arrived at PMV to assume the On-Scene Commander (OSC) role, as the source of the fuel oil spill was not yet confirmed. At 21:30h, the CCG boarded the suspected polluting vessel, the M/V Marathassa, to discuss the spill with the Captain. The CCG issued a notice requesting the vessel’s representatives’ intentions of how they planned to respond to the fuel oil emanating from the vessel, as per oil spill response protocols. The Captain denied the vessel was the source of the pollution.

Throughout the night, WCMRC continued to recover fuel oil from the water. Although the M/V Marathassa had not yet been confirmed as the polluter, WCMRC and CCG determined the need to boom the vessel at 03:25h after indications that fresh fuel oil was being discharged, which was completed by 05:25h. The first priority of any oil spill response is to control it at its source. By that time, a representative for the vessel continued to deny responsibility for the marine pollution and indicated that they would not be taking any actions.

By 07:00h, the CCG requested space at PMV to coordinate a response. Unified Command was officially established by the CCG as the lead agency, as the polluter was not willing or able to take action. Key partners, including the province of British Columbia and the City of Vancouver were already on scene.

Several aerial overflights were conducted throughout the day on April 9, including a National Aerial Surveillance Program (NASP) flight at 12:20h that estimated that there remained approximately 2800L of intermediate fuel oil on the water; however, this estimate did not include any recovered fuel oil from the previous night. By 18:06h it was estimated that the remaining fuel oil on the water had been reduced to 667L, due to recovery operations, evaporation, dispersion in the water and quantities being deposited on beaches, etc. International best practice of on-water oil spill recovery average rates in all weather conditions is 10-15% Footnote 12, but under ideal conditions the recovery rate could exceed this amount. Shoreline assessments were conducted, with reports of fuel oil at a variety of sites; however, no oiled wildlife was observed at this point.

M/V Marathassa

Type: Panamax-sized bulk grain carrier

Run by: Alassia NewShips Management Inc., based in Greece

Built: 2015

Flag: Cyprus

Deadweight tonnage: 81,000

Source: www.alassia.eu

The nature and amount of fuel oil released from the vessel will be the subject of further investigation by TC; however, for the purposes of the response operation it was estimated to be 2800L of intermediate fuel oil IFO 380 on the water, as of the morning of April 9. While the estimated quantity was shared with Unified Command partners, the suspected type of fuel oil was not. The working estimate of the total actual fuel oil recovered by WCMRC was 1400L. This is a subjective estimate by experienced oil spill responders based on the estimates of the quantity of oil collected on the water, accumulated on boom, the vessel, sorbent pads, etc.

This lack of critical information regarding the type and quantity of fuel oil impacted the flow of public information to the responsible parties and limited their ability to advise the public on precautionary measures. This was also a subject of much speculation regarding the potential cumulative effects of the polluting fuel oil product.

The CCG, through Unified Command, continued to coordinate the overall response effort. The level of effort was significant with an average of 75 people at Unified Command and up to 100 personnel working on the water and shoreline remediation on a daily basis.

Fortunately, the impact on wildlife was mitigated to the greatest extent possible and an effective response program was put in place. Environment Canada estimates 20 birds were impacted by the fuel oil, with one fatality and three successfully captured and rehabilitated prior to being released into their environment.

The M/V Marathassa was released on April 24 to continue her voyage. At that time, Unified Command was demobilizing and a response team was established to address any further clean-up efforts. The Project Management Office was established to continue working with First Nations and stakeholders on outstanding tasks. On April 25, the M/V Marathassa departed English Bay.

1.2 Factors at play

There were a multitude of factors surrounding the incident which influenced the operational response and should be acknowledged at the onset in order to have a more comprehensive understanding of the incident and how it unfolded.

Canada’s Marine Oil Spill Preparedness and Response Regime

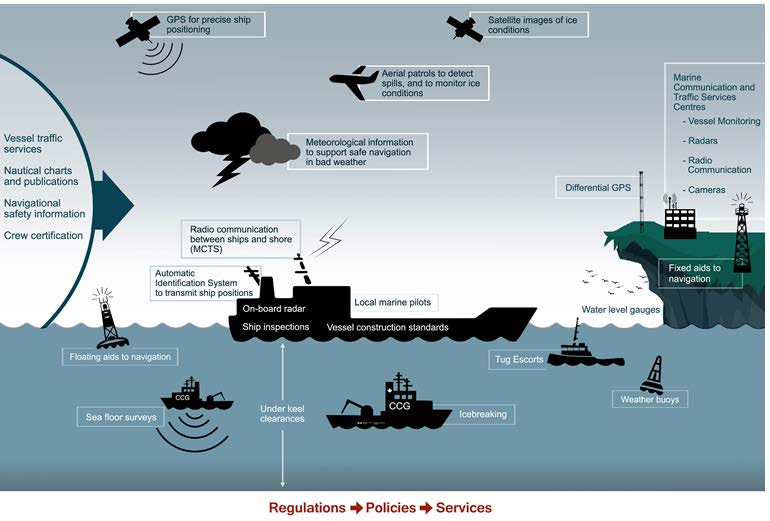

Graphical representation of marine oil spill prevention in Canada

Canada’s Marine Oil Spill Preparedness and Response Regime Footnote 13 is based on the ‘polluter pay principle’, which requires the polluter or the Responsible Party to take full responsibility for the cost of cleaning up any damages caused by an oil spill. This principle is supported by both industry and the federal government. Industry, through TC-certified Response Organizations, provides Canada’s primary response capability.

Within this regime, TC provides the legislative and regulatory framework. The CCG is legislated to oversee industry’s response to ship-source spills and manages the response when the polluter is unknown, unable or unwilling to respond, ensuring an appropriate response to all ship-source and mystery-source oil spills. EC provides the scientific, environmental and wildlife information and advice.

Since its creation in 1995, the regime has been successful at preventing and reducing the occurrence of oil spills in Canadian waters, due to the regulatory, prevention and operational measures in place. As such, the occurrence of large spills in Canada is rare compared to other international regimes Footnote 14, which has limited Canada’s exposure and experience in responding to large marine oil spills within Canada.

In the case of a mystery spill, the CCG is responsible for exercising leadership and managing the response in collaboration with partners and industry, as On-Scene-Commander (OSC). When the polluter is identified, the CCG advises the polluter of his or her responsibilities and asks for their intentions regarding oil spill response. If the polluter is willing and able, the CCG will monitor the polluter’s response, as the Federal Monitoring Role (FMO) to ensure that the response is appropriate. If the response is deemed inappropriate, the CCG will manage the response.

WCMRC, the TC-certified Response Organization for the Western Region, has a reputation for excellence and quick response. WCMRC’s response capacity exceeds the 10,000 tonne planning standard currently required by the Canada Shipping Act, 2001 Footnote 15 and TC’s Response Organization Standards. Footnote 16

As per a LOU, the port is responsible “to assess the size and nature of the spill and collect information that may assist CCG personnel with planning the appropriate response strategy” (Annex F). Legally, both parties are still able to respond and recover costs by accessing the vessel’s protection and indemnity insurance or the Ship-Source Oil Pollution Fund (SOPF). If the source of pollution is known, PMV would normally facilitate a response between the vessel and WCMRC. If the source of pollution is unknown and PMV determines there is recoverable oil, then the response would be handed over to the CCG. In both instances, the CCG would be involved, either as FMO, or OSC, respectively.

Since the regime relies on many partners, there is a necessity for those partners to work together to ensure an efficient, effective and successful response. In practical terms, this means partners from different organizations and jurisdictions taking an active role in monitoring, assessment, notification, overall leadership in an incident, response and environmental advice. Additionally, it is important to appropriately manage the relationship with the polluter to ensure that the primary focus is protecting public safety and minimizing damage to the marine environment.

Canadian Coast Guard’s Readiness, Resourcing and Exercising

The CCG’s Western Region, just prior to the incident, was demobilizing from a major oil recovery operation in the Grenville Channel, the Brigadier General Zalinski (BGZ). The majority of the staff were not available in the Vancouver area to respond directly. The certified Response Organization, WCMRC, was available and typically responds to spills in the port and in the province for the marine industry, as they represent Canada’s primary response capacity on the West Coast. Normally, the CCG’s role is to monitor, ensure an appropriate response, and assume command if the polluter is unknown, unwilling, or unable to respond. The CCG may contract the Response Organization or use its own resources to respond. In a major incident, all available industry, CCG vessels and emergency response capacity are mobilized.

The CCG’s Environmental Response (ER) Program in the Western Region is currently undergoing a significant staff turnover, and has lost long-term employees and expertise to attrition and other staffing opportunities. The program is currently comprised of a group of fifteen specialists; however, resources can be cascaded from other regions during major incidents in operational, technical and administrative positions. These jobs are demanding and require a high level of technical, management and leadership skills.

As there are few environmental incidents of significance in BC, the opportunity to engage and exercise leadership with partners and practice respective roles and responsibilities in an emergency is limited. It was noted by partners that real life responses are often more challenging amongst the federal, First Nations, provincial and municipal players than when exercised.

The CCG’s approach to incident management has been characterized in a positive manner by partners as being inclusive. However, in the case of the M/V Marathassa response effort, this inclusive approach also increased the number of participants in Unified Command, many of whom were not familiar with ICS and oil spill response. In effect, this blended the Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) and Incident Command Post (ICP) causing confusion and a lack of clarity at times for all involved.

Geography and Weather

English Bay is located in Vancouver, BC and borders on a densely populated area with numerous high rise buildings. Metro Vancouver is surrounded by 21 municipalities Footnote 17, four of which were affected by the M/V Marathassa spill. Any spill of persistent fuel oil, such as in the case of the M/V Marathassa, will be detected quickly and an immediate, coordinated approach is expected. Additionally, PMV is the third largest tonnage port in North America and the busiest one in Canada. There is also significant recreational and leisure usage of the port given the year-round boating season and the public access to its waters.

Although the probability is low, according to an independent risk assessment Footnote 18 commissioned by Transport Canada, this spill was statistically likely to occur. The risk assessment indicated there was a low probability of a significant oil spill on BC’s coast, but if one were to happen, it would most likely occur around the southern tip of Vancouver Island. Therefore, the need to improve the “readiness to respond” and the overall preparedness of the regime is important.

During the first hours of the assessment, the sea state was relatively calm. Due to the calm sea state and the background lighting from the city, WCMRC was able to skim and deploy boom throughout the night. Typically, operations cannot be conducted throughout the night; therefore, this was a unique and well-executed component of the response.

Public and Political Sensitivities

The general public’s awareness of oil transportation and marine safety in Canada has been increasing, particularly given the heightened sensitivity related to proposed pipeline expansions and other oil-related projects emerging in Canada.

This translated into an increased level of interest from the public regarding all aspects of the response efforts. In particular, this increased the demands for information and prudent recommendations from the Environmental Unit (EU) based on solid science.

While it was noted by the majority of partners that the operational response to the incident was well-executed, the media attention and the lack of immediate accurate information created additional demands for information which interfered with the management of the incident.

Way Forward

In this incident, the partners, most notably the First Nations and local governments, commented that although they have been observers in some regulatory exercises, they have rarely been active participants in oil spill exercises. The Tanker Safety Expert Panel’s (TSEP) report released in December 2013 identified the need to increase federal government engagement with key partners as part of what they termed ‘Area Response Planning’ (ARP). The Government of Canada has adopted the ARP model, a new planning methodology that brings together more partners to develop response plans. ARP is being piloted in four areas across the country, including the southern portion of BC. This model will be beneficial in preparing for any future incidents.

- Date modified: